Inequality, Climate Change and War. A Time to Rethink Inflation

Inflation is a complex problem that needs a deeper look, especially when the current times are all but normal. Too much of the common narrative is around one average rate of price increases, which can be either caused by disruptions in the supply of goods and services or by a rapid increase in purchasing power. If it is the latter, the solution is always increasing one broad-based interest rate and asking government to cut spending. If it is the former, the solution is the same, it just takes longer to convince everyone to use that hammer and hit the nail.

If we start unpacking a complex problem such as inflation – as it is common in business and most academic disciplines – one would find a much richer set of causes, consequences, and therefore solutions.

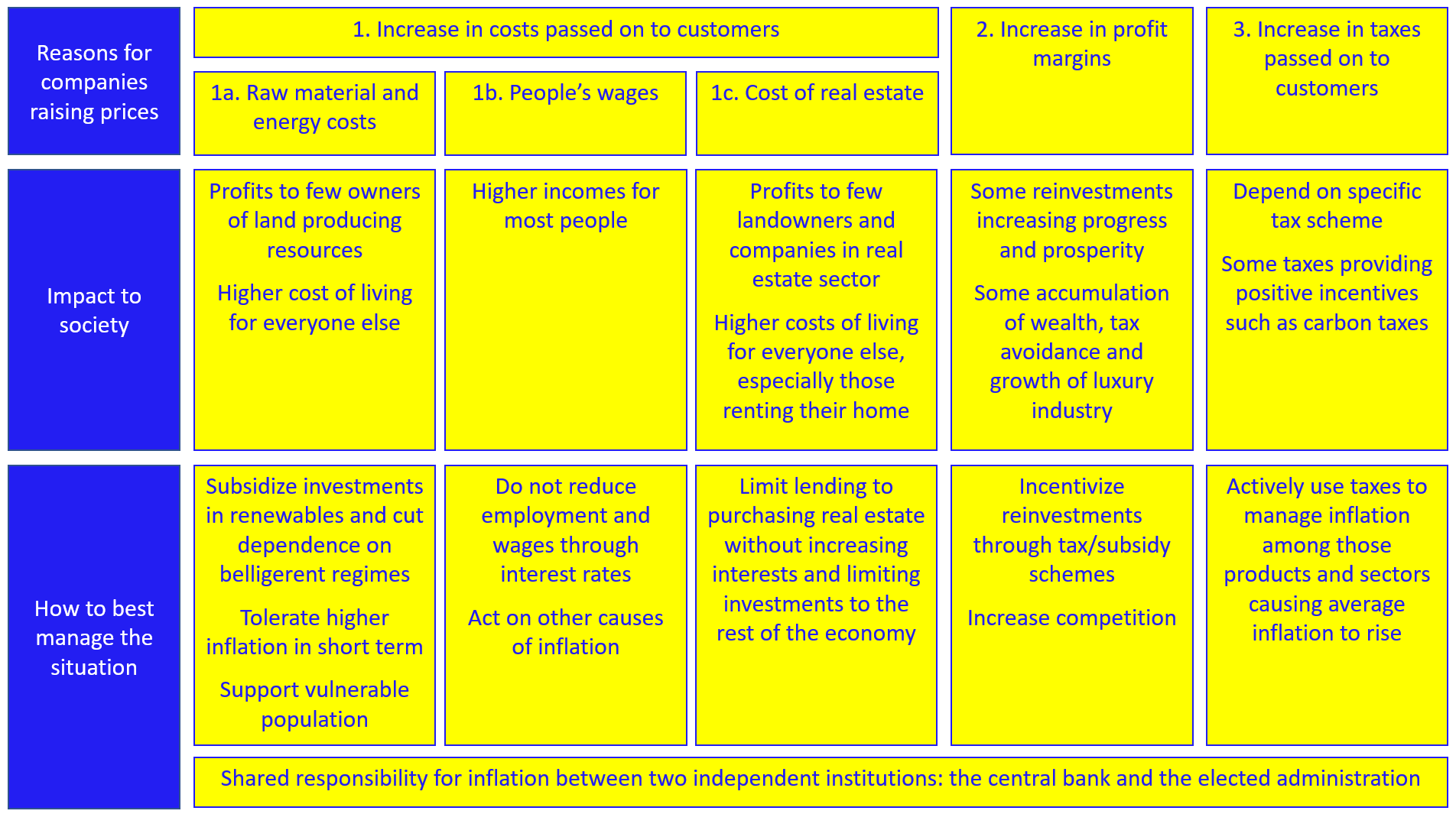

In practical terms – which means in the reality of companies and how they make pricing decisions – inflation can be explained by either 1) an increase in the cost of inputs for a company that is passed to consumers, or 2) by the increase in the profit margins of companies, or 3) by an increase in taxes that could hit either inputs or profits and trigger companies to raise prices accordingly. For the cost of inputs, it is useful to further break it down into 1a) the costs of raw material and energy, 1b) People’s wages, and 1c) the cost of the commercial real estate that most businesses require. If not obvious, it is the decision of companies to increase prices without changes in quality that technically leads to an increase in average prices, inflation.

Looking at each of these five channels to companies increasing prices one can assess the consequences of and best solutions to each. Unsurprisingly, the picture is more nuanced than the typical “all inflation is bad”: Some inflation channels have an overall positive impact on most people and society would gain from letting some of these channels play out whilst blocking others that have only a negative impact on living standards.

For the channel of raw material and energy, the consequences for society from increased prices are generally negative given the only beneficiaries are the relatively few owners of the land which produces such resources. The best way to counter this type of inflation though is to rapidly increase the supply, which is the opposite of the incentive generated by the typical increase of interest rates or austerity. Using strategic reserves to smoothen temporary price shocks can only help in the short term. But solving the energy crisis once and for all is one of the major strategic goals of the 21st century. A green deal subsidizing renewable energy investments and their consumption among low and middle-income families can get us there faster. This goal cannot be sacrificed for the sake of keeping inflation low. Society needs to move away from fossil fuels, and Western democracies can finally halt their dependency on resource-rich autocratic regimes whereby the sales of such resources finance the military of these regimes to act against their own population or neighboring ones. Inflation of the price of energy in times of inequality, climate change and war must be fought with unprecedented subsidies to renewable energies, potentially tolerating higher short- term inflation.

For the channel of people’s wages, the situation is quite different. We live with high inequality in much of the developed world and a persistent lag of wage growth for much of the population. If wage growth was the only cause of inflation, it should be a reason for celebration. Price inflation would, by definition, be equal or lower than wage growth. But indeed wage growth is never the only cause of inflation and, therefore, average inflation rates have exceeded wage growth most times in the last 40 years in OECD countries. The only exceptions: the top 10% highest earners and the post-Covid years where in some countries such as the US, for the first time in a long time, low-wage earners are seeing raises significantly stronger than inflation. Nurses, teachers, truck drivers or hospitality workers that are seeing wage growth these days have been penalized for the last 40 years. We need to overcome the common narrative that wages will pass on to prices in a race that is never good for workers. This is only true when there are other sources of inflation and those are the ones that need action. Curbing employment and wages by slowing down the economy through austerity and higher interest rates is not an answer conducive to a better society.

For the cost of commercial spaces, whether through rents or acquisition of building and facilities, the societal consequences are similar to raw materials and energy: very few landowners and real estate companies benefit while most businesses, their employees, customers as well as individual tenants are adversely affected. The standard measure of increasing interest rates could help fix this. Increasing interest rates leads to higher cost for mortgages that if sustained, would make it unaffordable to purchase high-value real estates. Domestic and commercial real estate prices would have to fall, and so would rents and the pressure on family budgets and on inflation. In the process though, higher interest rates would also reduce investments and have a hoard of other secondary effects with a long history of causing recessions. A much faster solution? Regulate financial institutions to limit the financing of real estate. This can be achieved by higher loan to value ratios or higher reserve requirements for banks’ mortgage or by banning banks to repossess collaterals. This is likely to cause a crash in the housing market but…doesn’t society benefit from houses that don’t take 40 years to repay for the average worker, or 60% of a persons’ income in rent?

Shifting to the channel of increased profit margins, the consequences on society are diverse. On one end, higher profits lead to higher returns to shareholders. Much of the profits are accrued to a small portion of the population but a good chunk also accrues to funds responsible for pensions’ savings. Equally nuanced is the benefit on investments, as some companies in some industries would really create value to society from reinvesting those higher profits in innovation. Others are instead raking in huge profits for a handful of shareholders and often in offshore accounts, fueling lavish lifestyles enabled by tax evasion. The best solution here – as I suggest in my book “Outgrowing Capitalism” – is to create a tax system that penalizes excessive profit margins and provides incentives to companies that reinvest higher profits. Today, it is companies increasing profit margins that seem to be one of the main causes of inflation. Some blame it on monopoly effects of concentration, others on the temporary low competition from imports given the Covid-related disruptions. Either way, adequate incentives could turn those profits into productive investments. It seems neither strategic nor sensible if we instead resort to increasing interests and cause a recession, just because some companies have the power to command huge profits.

And lastly, government taxes do also have an impact but consequences and solutions are also nuanced. For example, carbon taxes clearly have a higher purpose that one would place above fighting inflation. Of course, a government could give carbon tax credit instead but not all governments have fiscal space to do so. Other taxes might be more or less beneficial but it’s up to governments to play their game and voters to judge them with their votes. Let’s not forget that higher taxes are also a way to cool down an economy and inflation by reducing the purchasing power of people or companies. And contrary to interest rates – which take time to act and reduce investment in the process – taxes can be much more targeted and have a rapid impact. Raising VAT on selected products that exhibit inflation such as housing, luxury goods, goods with high import components or carbon emissions are likely to reduce pre-tax inflation pressures without affecting investments in other sectors. Creating new tax schemes designed to fight inflation such as what I proposed above can be part of the solution to inflation, instead of the cause.

To some extent this more granular and real-life analysis is happening: central banks do measure inflation at the product level and separate inflation caused by imports of commodities that aren’t best tackled with domestic monetary policies. And they have started looking at wages and employment by race and by income or skill level, a useful move to avoid vulnerable segments of the population are left behind because the rich are splurging. But central banks are still left without tools to adequately tackle inflation on a channel-by-channel and product-by-product basis. We need to go beyond the idea that central banks’ independence means central banks should fix inflation alone. Governments need to contribute to and be held responsible for excessive inflation. Once this full separation of responsibility is substituted by collaboration of two independent institutions – central bank and elected administrations – for a common goal, many more of these solutions can be explored and we might see the end of these periodic booms and busts that hold society back and penalize the most vulnerable. And through the right subsidies and taxes, we might be able to defeat climate change and stop buying oil and gas from belligerent regimes.